Love, in the Time of Cancer

A Story About Illness, Intuition, and the Man Who Helped Me Pack.

The last thing I packed was a jade plant with brittle roots and too many dead leaves. It didn’t deserve the journey, but neither did I. There are no ceremonies for this kind of departure. No paper plate sendoffs, no farewell brunches. Cancer is not a promotion. It is not a wedding or a job transfer. It is not a time to be toasted. It is, more often, the kind of private apocalypse that makes people quietly look down at their phones. Or, worse, try to find something upbeat to say. “You’ve got this!” I didn’t have it. It had me.

There were no goodbyes. No one waved. No one called. I hadn’t told many people. That part is important. When you leave like that, people assume you’ll be back. Or that you’ve gone somewhere trivial. Somewhere forgettable. A spa. A writer’s retreat. No one suspects cancer.

I packed my life in silence. And when it was done, I turned off the lights and left Phoenix as if slipping out of a hotel room where I’d overstayed my welcome. Quiet. Undisturbed. Unclaimed.

I’d met him a month before, this man with hunting knives and eyes like Wyoming dusk. Long-distance flirtation. Farmers Only DMs turned into late-night phone calls. I told him I liked the way he spoke in verbs. He told me he could build a fire with wet wood. I believed him.

Then: the diagnosis. Rectal cancer. Stage I-don’t-know-yet-because-I-wasn’t-brave-enough-to-wait-for-the-full-report. The kind of sentence that ends a chapter, or starts a very different book. I didn’t tell him to run. I didn’t need to. I was already moving—out of my body, out of my lease, out of my life in Arizona. He didn’t run. He offered Idaho. Swan Valley.

I drove up in September with my dog, the one creature who had seen me fall apart enough times to know not to flinch. The air changed with each mile. Drier, cooler. Like even the molecules knew I needed something softer.

He greeted me in jeans stained with saw dust and the kind of smile that made you want to say yes to things you weren’t sure you deserved. And he looked—how can I put it—capable. Not in the way men with apps and opinions like to seem capable. But in the older, quieter way. Like if your life suddenly went to shit, this is the man who would pull you out of the snowbank with his bare hands and a stubborn belief that anything worth loving should be carried, not abandoned.

A week later we were in Phoenix, packing up the old life.

There is no romantic way to pack up your life in a cancer diagnosis. There is only the grief of sorting what version of yourself gets to come with you. What makes the cut. What you throw in the trash without looking at too closely. It wasn’t the first time I’d packed like this. The first time was after my mother died. I left Minneapolis the way someone leaves a burning building—grabbing what I could carry, coughing through the smoke, trying not to look back at the parts of myself still smoldering inside. Phoenix was the destination then. Healing, maybe. A new start. That’s what people say when they don’t know what else to call running.

That was the first time. This was the second.

We packed in silence. Not the heavy kind. The reverent kind. He helped me lift boxes. He didn’t ask what was in them. That was something I appreciated. I remember crying in bed the night before, curled like punctuation, trying to become small enough to disappear between the sheets. He pulled me close and said things that made space for breath. Whispered, “This isn’t your fault,” and “You don’t have to be strong for me,” and “We’re going to build something new.”

He meant it. And that terrified me more than the diagnosis.

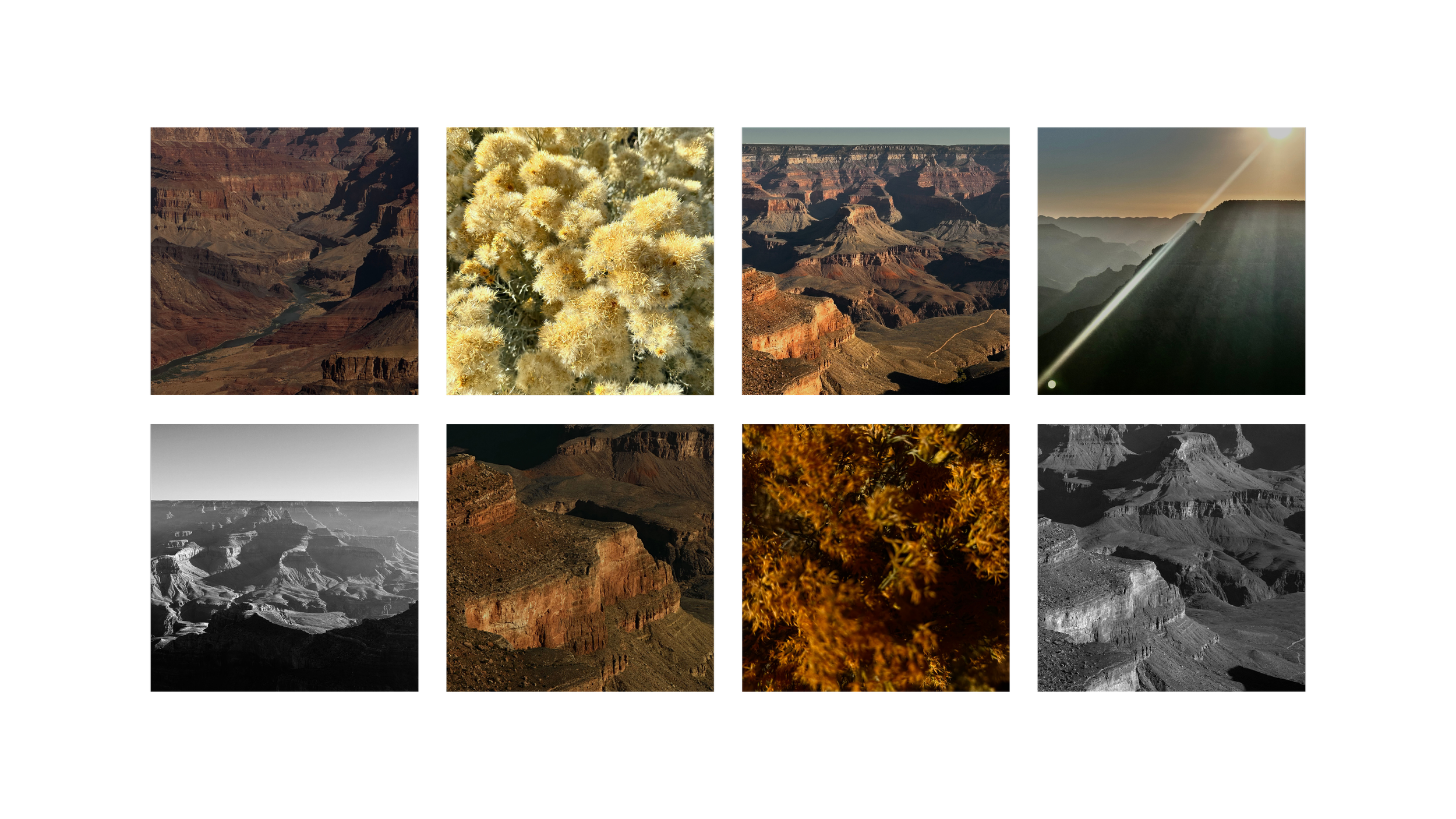

We stopped at the Grand Canyon on our way north. He stood close to the edge. I kept back. I didn’t trust the ground, or myself. I looked into that great gash in the earth and thought: This is what I must look like inside now. This is what grief has done to my body. Layer upon layer of erosion, silence, and time.

On the drive, we listened to a podcast about a woman who faked cancer. Her voice played through the speakers like a ghost’s. I laughed, though it didn’t feel quite like laughter. He turned to me and said, “You’re the real thing.”

I nodded. But I wanted to ask—and what if I wasn’t? Would you still stay? I didn’t ask. Some things are best left unanswered.

Swan Valley is not what people imagine. It is not idyllic. It is not cruel. It is a quiet place, which is a different thing altogether. The kind of place where the silence follows you from room to room.

Not unfriendly, just observant. Not a place you move to—A place you retreat to. A valley shaped like a cupped hand. Holding you. Humbling you. The mountains don’t care about your résumé. The elk don’t care about your prognosis. There is peace in that indifference.

In the beginning, we lived out of suitcases. Like fugitives. Not from the law, but from the lives we used to live. The farmhouse—cracked, drafty, and once owned by a writer named Afton Bitton (who I imagined wore aprons and held onto secrets the way some women hold onto pickling recipes)—creaked in its bones each night. As though it, too, was learning how to hold us.

We placed our clothes over chair backs. Our toiletries in mismatched bowls. Nothing was folded. Nothing was put away. That was the silent agreement. We wouldn’t pretend we belonged there. Not yet. We were still waiting to see if we were staying or simply passing through like smoke through the valley. Swan Valley. The name itself a contradiction. Soft in the mouth. Hard in the winter.

Outside, the world wore its best colors. As if to say—here, even in rot, there is beauty. The aspens turned the color of old postcards. Elk wandered out like priests from another religion. The mountains stood back and watched. Uninterested in our little dramas.

We kept to a schedule built from the soft, slow scaffolding of rural life: grocery runs, Sunday night dinners at his parents house, gas for the truck. The Hunter moved slow. Stiff with new scars. He had just had back surgery. I had just had the rest of my life cracked open like a soft-boiled egg. We were both broken in places we couldn’t see. But we didn’t speak of pain. We passed it back and forth like a shared blanket. Quietly. Reverently. Sometimes, he drove his truck while I stuck my head out the window like a child—or a dog—camera in hand, desperate to capture what might not last: the way the light hit the grass. The way nothing was expected of me in that moment. The way silence settled over the land like permission.

I signed up for yoga teacher training. Then sculpt training at a yoga studio in Jackson. I didn’t want a certificate. I wanted a ritual. I wanted something to do with my body that wasn’t survival. To sweat on purpose. To hold something—not grief—but a pose. A breath. A goddamn plank.

I went went horseback riding with his youngest daughter, through fields that whispered their past. We picked apples from trees older than our grandparents. We drove through Palisades like we were tracing the veins of our past. There were days we said nothing at all. And it was enough.

And then—the unthinkable. Thanksgiving. Christmas. The holidays arrived without ceremony. There was no plan. No declaration. One morning there were pumpkins on the porch, and then one day it snowed. That was all.

For the first time since my mother tied the final knot, I had somewhere to go. A table that had a seat with my name on it, even if no one said it out loud. There was no fanfare. No grand declarations of family or fate. Just a quiet dinner. For Thanksgiving, I cooked like a woman possessed—my grandmother’s twice-baked mashed potatoes, a pecan pie that cracked at the edges like old family secrets, a Dutch apple pie that steamed up the farmhouse windows with cinnamon and grief. I made a tomato pie with a lattice crust so intricate it felt like prayer. I made too many pies, really.

The Hunter bought me snow pants and boots. I had none. Seven years in the desert leaves you unprepared in ways you don’t expect. He didn’t say much—just placed the box on the table. That was his way.

We cut down a Nordmann fir from the forest, dragged it home like pilgrims. I decorated it with tinsel and pink ribbon, strands of defiance and beauty, one loop at a time. We went sledding with his children and their children. Generations folded into one snow-drenched afternoon, laughter carving through cold air like birdsong.

We took in a Swan Valley holiday parade, the route was modest, stretching just a mile up and down the highway, mirroring the quaintness of Swan Valley itself. Floats ambled by on the backs of backhoe loaders. Horses moved like elders in a procession. Dapple Percherons, black Morgans, and brown paints adorned with Christmas bows and LED lights walked past. Some sauntered. Some took proud deliberate steps. Some swayed from side to side like they were walking out of the Road House diner behind us. It was sparse. But it was ours.

We went Christmas shopping. He snuck mittens and a windshield scraper into the cart. I pretended not to notice, and loved him for his practicality. On Christmas morning, we went duck hunting. I mistook the decoys for targets. He laughed—hard. A full-bodied, gut-deep kind of laughter that startled the ducks and made me drop my glove in the snow. I laughed too, the kind of laugh that leaves a mark, the kind you forget your body can still remember after it’s been through ruin. It wasn’t grace, exactly. But it was close.

And somehow, that laughter opened the door to Christmas. The house filled slowly. First came the Hunter’s children, then his grandchildren, a chaos of elbows and candy miniature cowboy boots. His brother arrived next, then his brother’s children–feral and sugar-drunk, high on stockings and hope, their faces shining like just-polished ornaments. I watched them pile onto the couch, a sea of little limbs and torn paper, the plastic cover beneath them crackling like some kind of ridiculous symphony. One of them handed me a candy cane without making eye contact, and it felt like being knighted.

His father was in the corner, quiet as a mountain. Observing. Enduring. Holding space like men of his era were taught to do—silently, stoically, without fuss.

We gathered in the living room around the tree, a taller thinner Nordmann fir we had cut down with his folks the same day we found ours. It tilted slightly, unapologetically. I liked it for that. Beneath it, the presents had bloomed—unnecessarily generous, wrapped with a kind of urgent tenderness, as if the givers feared this might be the last year we all made it.

He snuck me gifts again. Spark plugs. Kinesio tape for my knees after the sculpt training. A pair of socks so thick I could finally walk on the icy floors without wincing. He didn’t ask if I liked them. He knew I needed them. And there’s a kind of love in that—practical, unfussy, real. The kind that says you don’t have to sparkle, you just have to stay alive.

I watched them all—his people. This family stitched together by time and second chances. I didn’t speak much. But I saw everything. The way his daughter-in-law brushed lint from her toddler’s sweater. The way his grandson offered him a wrapped Nerf gun like it was an heirloom. The way he looked at me across the room and didn’t need to smile for me to feel it.

The thing about Swan Valley is it’s named for it’s Trumpeter Swans. Big, encroaching, graceful creatures with alabaster plumage and the kind of slow, deliberate necks that make you believe in poetry again. They dot the farmland and glacial runoff even in the dead of winter like brushstrokes in a Monet painting—startling and serene all at once. They are too elegant for this brutal land. And yet they belong here more than I do.

The valley holds them. Feeds them. Offers up just enough thawed earth in the marshy edges for roosting. Occasionally, in the white quiet of winter, a handful of Bewick’s swans appear like ghosts that wandered too far from their own mythologies. You can find them at dawn, if you look. Or rather, if you listen. Their voices—deep and mournful like foghorns—echo off the hills just before the sun spills over the ridge. But you hardly notice the sound. What you see, what stops you, is how they move when they take flight. How all that heaviness, all that body, lifts. How it becomes grace.

They taught me that home is something you embody before it’s a place you land. And I needed to learn that.

And then there is Baldy.

Baldy, the mountain that stands watch like an old soldier—scarred, stoic, slightly hunched, but still holding the line. He’s not the most impressive peak in Idaho, but he’s the one everyone talks about. Not because he’s flashy, but because he’s always there. You wake up and he’s there. The snow falls and he’s still there. You drive to the post office for a $9 roll of stamps and he’s waiting for you on the way home, unchanged, unmoved, and maybe a little tired of your drama.

Below Baldy, the rolling hills unfold like a prayer whispered through farmland. They ripple out in soft, muscular humps—green in the spring, gold in the fall, white and brittle by mid-November. Tractors rest there. Old ones. Not put out to pasture so much as absorbed by it. Rusting beautifully in the sun like they’ve done enough. If you’re lucky, you’ll catch that light just right—when it hits the ridge and the metal glows like a secret someone meant to keep but told anyway.

There are only 346 people in this town if you believe google. Only 204 if you believe the population signs in Swan Valley. There are precisely three gas stations. A handful of bars. A church or two, all politely understated. A general store where the coffee tastes like 1994 and the concrete floors carry the weight of every boot that ever wandered in, lost or looking. There’s no pharmacy. No hospital. Just neighbors. And the knowledge that if your truck stalls on the pass, someone will come. Maybe not quickly. But they’ll come.

It’s quiet here. Not just audibly, but spiritually. The kind of quiet that lets your thoughts rise to the surface without shame. It doesn’t ask anything of you, Swan Valley. But it sees everything. Your intentions. Your weight. Your longing. And it holds them all like the river holds the swans—not tightly, but completely. That is, unless you’ve already handed them over to the town gossip, in which case—God help you.

The winters are harsh and brittle, yes. The wind cuts sideways. The snow stacks itself into walls that take weeks to melt. The roads close without warning. The mail gets delayed. Your fingers crack from the cold. Pipes groan like old men in church pews. And still—people stay. They hunker. They mend. They rise early. They check in on each other with the kind of care that’s too real to be called kindness. It’s older than kindness. It’s need.

Civilization is a stretch in either direction. Jackson, Wyoming—just over the pass—is a scenic hour if you like your groceries to cost twice what they should and your coffee to come with oat milk and resentment. That pass, by the way, is more than just a road. It's the artery to Jackson—the lifeblood of the city’s service industry. When it closes (and it does), the whole ecosystem shudders. Deliveries stall. Tips dry up. Jackson eats itself. Idaho Falls lies westward, a sprawl of big-box stores and fluorescent-light sadness. The kind of place where dreams go to die next to the seasonal aisle at Target. But here, in Swan Valley, you get the feeling the world has stopped spinning quite so fast. The mountains don’t care about your schedule. The air is cleaner for it. And if you listen closely, you can almost hear yourself again. Named one of the most beautiful towns in Idaho. And not just in the Chamber of Commerce way. In the honest way. The kind of beauty that isn’t performative. The kind that sneaks up on you in the middle of a Tuesday, when the clouds hang low and the horses are standing just so in the field, and you realize—for the first time in maybe months—you aren’t waiting to run.

A blog post by Rachel Smak on grief, loss, and lessons from stage 3C rectal cancer